How to make the first open source contributions

In the last few years, I have had the opportunity to contribute to several open-source projects. It has been an enjoyable journey, but looking back I spent countless hours trying to figure out where to start, what I could contribute, and how the whole process worked.

After some years of contributing to different projects, I collected some tips that made this process more straightforward and enjoyable.

Motivation

The first and most important tip is to find a project that gives me motivation. Many open-source projects contain hundreds of thousands of lines of code, with logic that can be difficult to understand at first. So, when choosing a new project to contribute, I search for the following:

-

Familiarity: It is easier to work on a project I am familiar with. For example, since I work a lot with Go, contributing to a Go library I frequently use helps me a lot since I already understand many aspects of the code and its purpose.

-

Passion: The process of contributing often involves spending hours trying to understand code that initially doesn't make sense. Being passionate about the project keeps me motivated to overcome the challenges that come with trying to understand the code.

By selecting a project I am familiar with and passionate about, I can keep my motivation and make meaningful contributions without giving up.

The Contribution Process

Most of the open-source projects are hosted on GitHub, where contributions are made through pull requests, and the issues are tracked through GitHub issues, so before starting, it is important to be familiar with Git, GitHub, Issues, Pull Requests, Forks, Commits, Code review, etc.

Here's a high-level overview of the process:

- Read the

CONTRIBUTING.mdfile: Many projects include aCONTRIBUTING.mdfile containing guidelines on how to contribute. This file may contain rules about things like commit messages and coding standards. - Find an issue that has to be fixed: There are lots of ways to identify the problems on a repository, which I will mention later in this blog post.

- Fork and Clone the Repository: Once I have found an issue I'd like to work on, I fork the repository, clone it to my machine, and start working on the changes.

- Submit a Pull Request: After making the changes, it is time to submit a pull request for review. The maintainers will review the code, and once it's approved, the maintainers will merge it into the default branch of the repository.

How to find an issue to work on

After opening a repository and searching on GitHub issues, there is a low possibility to find something I understand or have the skills to fix at this time since I might not be familiar with the project. For this purpose, I have discovered five other ways to identify issues, understand them, and being able to fix them. Below, I will mention some of them, along with examples of actual contributions.

Typos

A great first step is to start small. Many projects have documentation with minor spelling or grammar mistakes. Fixing a typo may seem trivial, but it allows me to become familiar with the contribution workflow without diving into complex code right away.

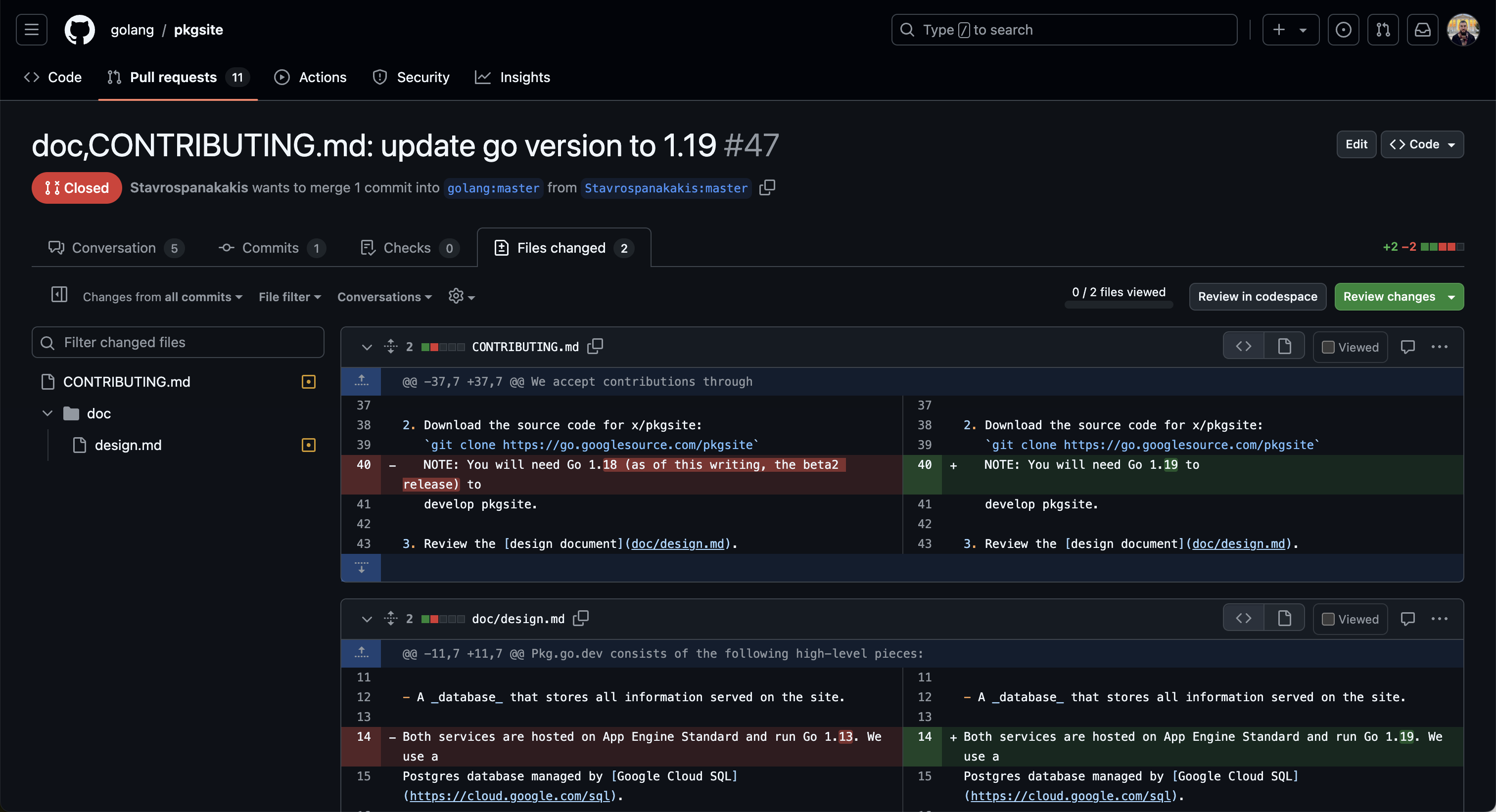

For example, contributing to the ecosystem

of the Go programming language is complex since

they do not only use GitHub but also use

Gerrit Code Review.

I was not familiar with it so after searching into

golang/pkgsite

repository, I found some outdated instructions, so

I opened a pull request to update them. Seems

pretty trivial but it was enough to get started

and understand how the Go team works and maintains

the Go programming language.

"Good First Issue" Label

Many projects label certain issues as

good first issue on GitHub. These issues are

typically less complex, making them perfect for

the first contribution to a project. Contributing to

a good first issue allows me to learn the project's

contribution process while solving a problem

that's easy to understand.

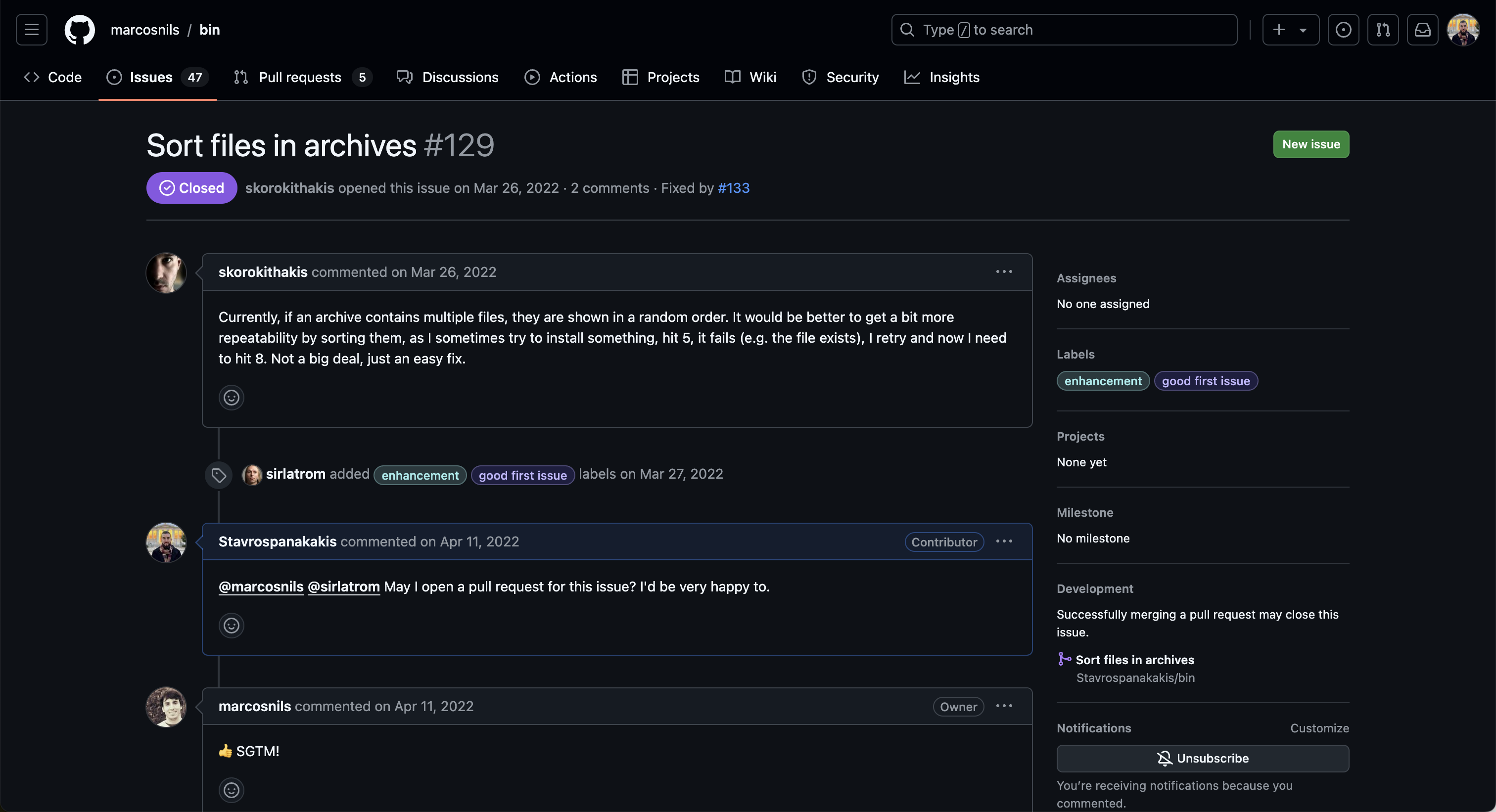

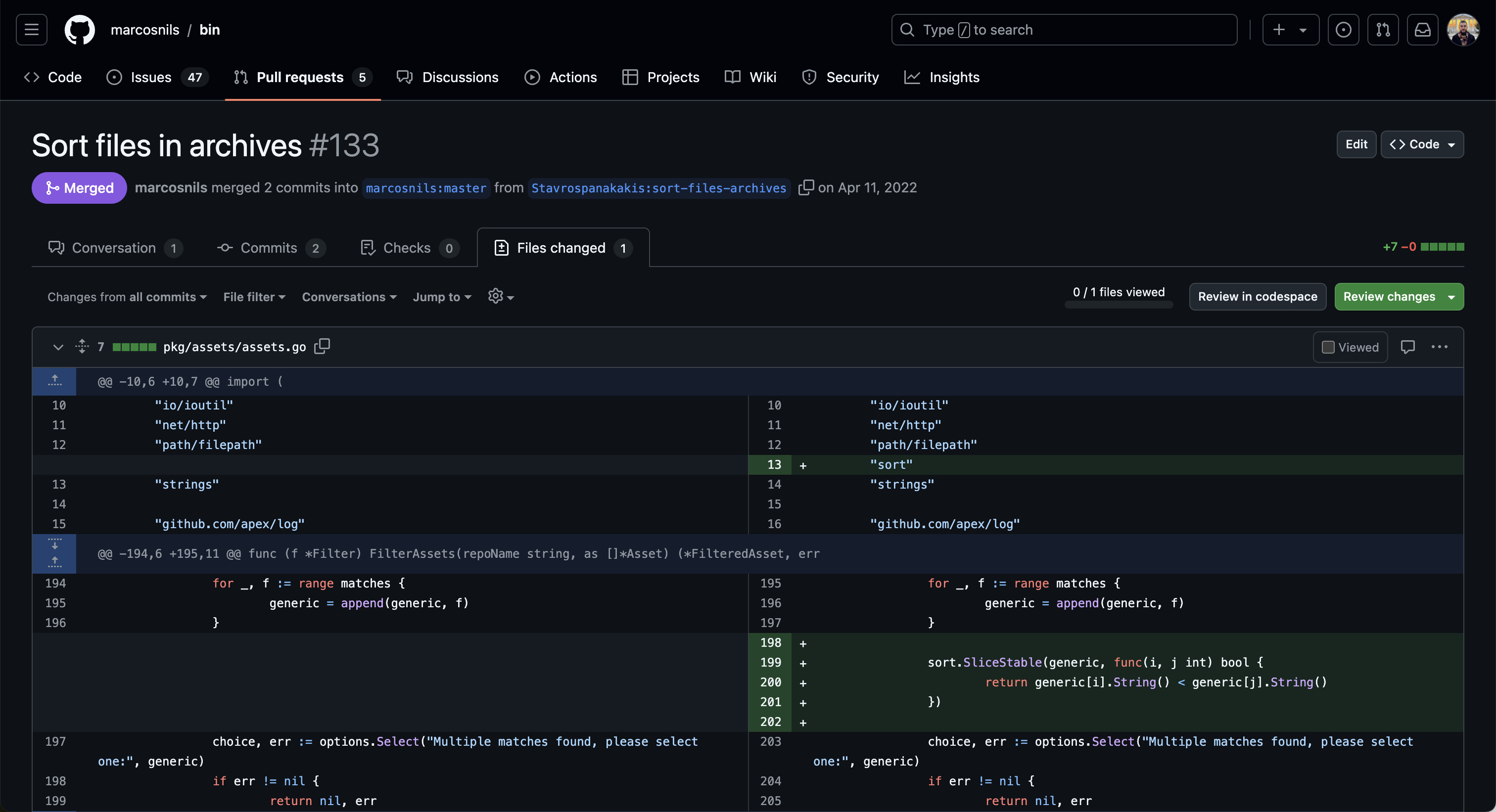

For example, there is a package manager that I use

called bin that is hosted under

marcosnils/bin

repository. This is a project I like and want

to contribute. After opening GitHub issues and searching

for an issue with a good first issue label, I asked the

maintainers if I could work on this.

This was an easy change since I only had to add three lines of code that were sorting a slice of strings.

TODO comments

Searching a codebase for TODO: comments

can be another great way to find things that

need attention. These comments often represent

areas of the code that the maintainers want

to improve or issues they still need to address.

These tasks can be a good starting point,

especially if I want to dig into the codebase.

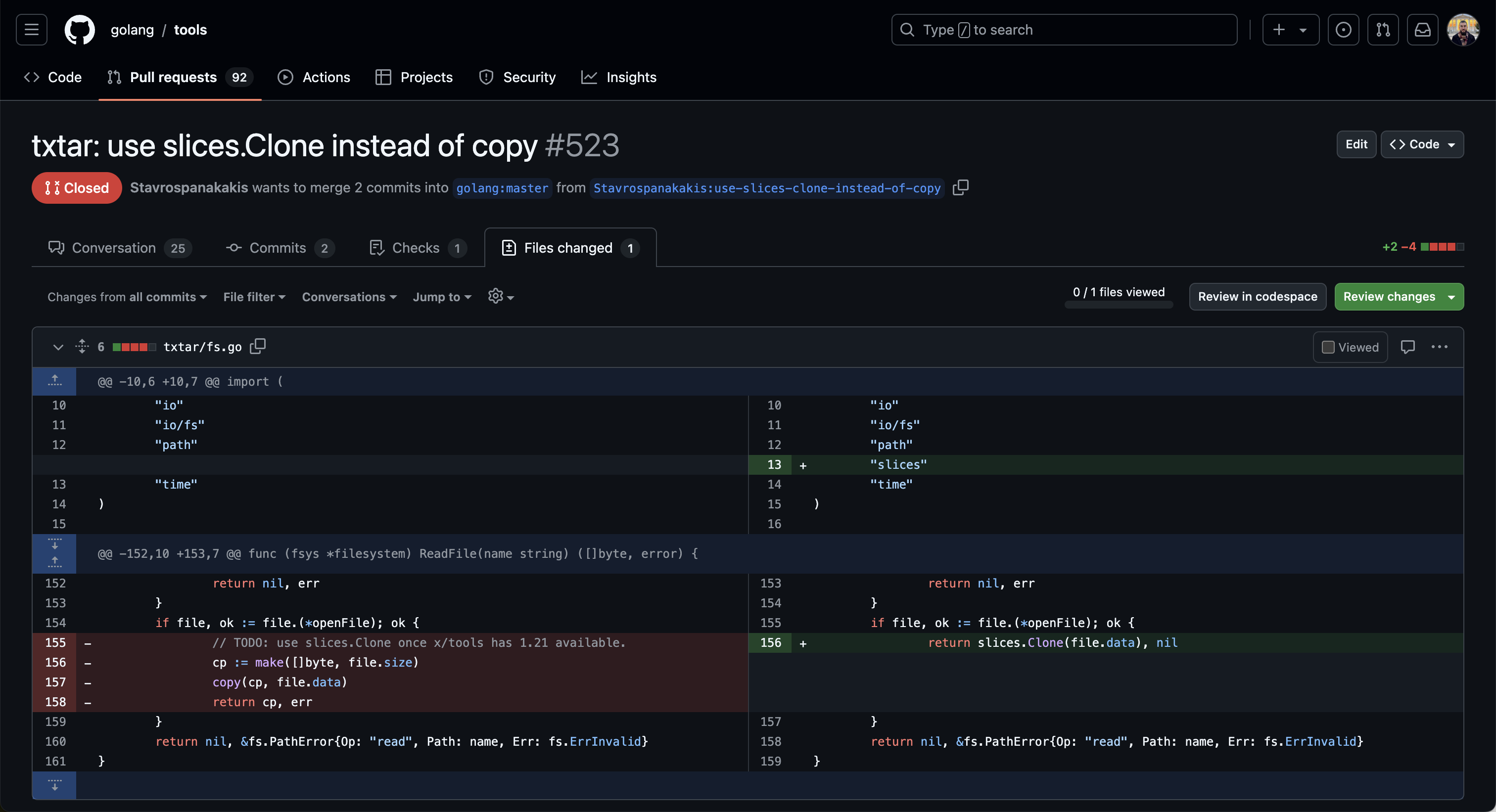

For example, I searched the term TODO: on

the golang/tools

repository and found the following code.

if file, ok := file.(*openFile); ok {

// TODO: use slices.Clone once x/tools has 1.21 available.

cp := make([]byte, file.size)

copy(cp, file.data)

return cp, err

}

I understood that this comment was written

before Go 1.21 was available. After looking at

the go.mod file, I saw that the version

of the project was 1.22. As a result,

I opened a pull request that was replacing

copy with slices.Clone.

Tests

Testing is crucial in any project, yet many open-source repositories lack decent test coverage. Writing tests is not only a great way to contribute, but it’s also one of the best ways to understand a codebase. You’ll be surprised by how much you can learn about the project just by testing its functionality.

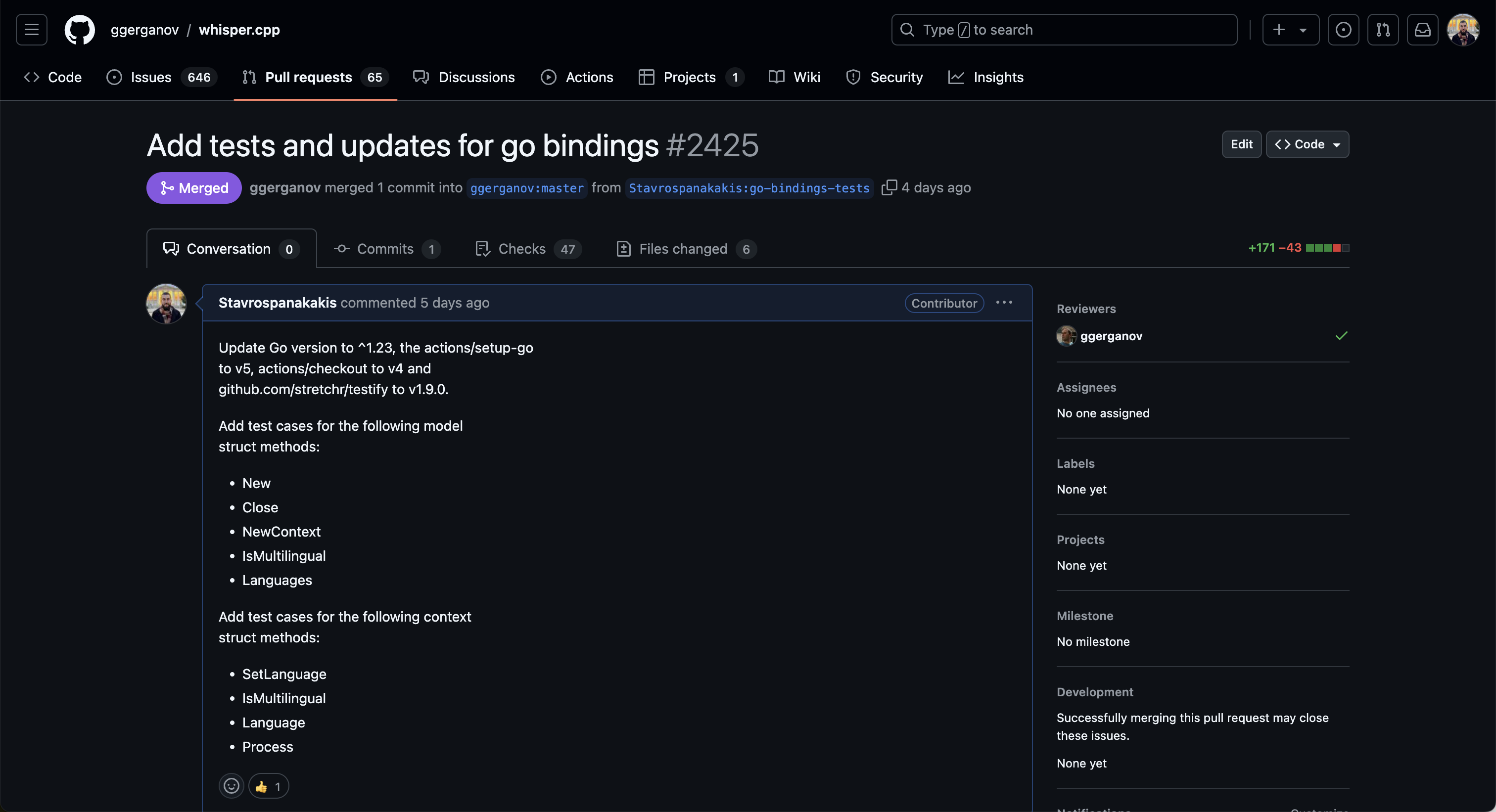

For example, after digging into the

ggerganov/whisper.cpp

codebase to search for the Go bindings of the C++

code of Whisper AI, I realized that many methods

did not contain tests. For this reason, I opened

a pull request that improved the test

coverage of the project.

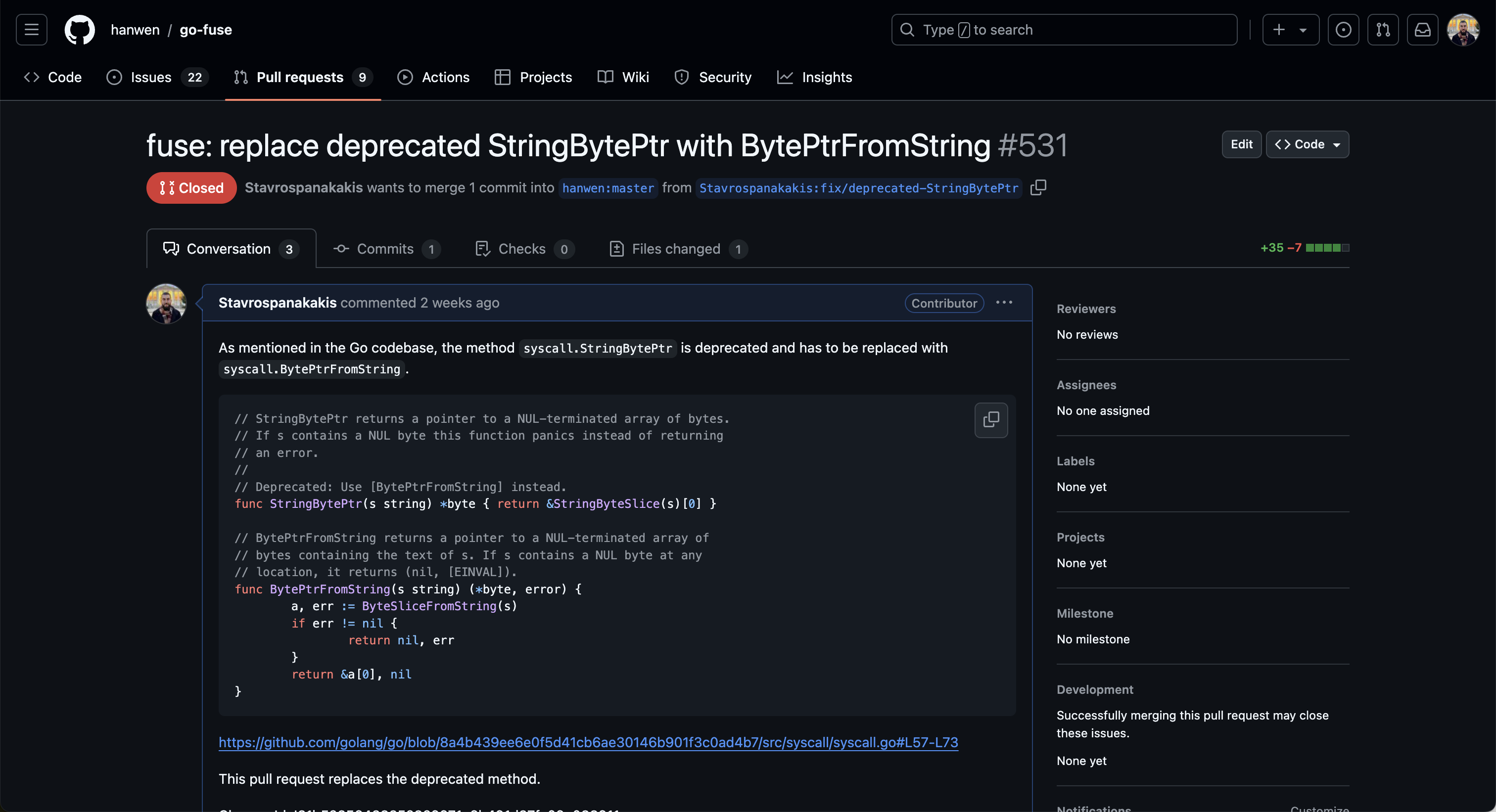

Deprecated methods

Many codebases contain deprecated methods

that need to be replaced. Searching for

the term Deprecated in the project

helped me identify such methods. Replacing

deprecated methods with updated alternatives

can be a valuable contribution that improves the

overall health of the project.

For example, by searching for the term Deprecated

in the golang/go

repository, I found the following code:

// StringByteSlice converts a string to a NUL-terminated []byte,

// If s contains a NUL byte this function panics instead of

// returning an error.

//

// Deprecated: Use ByteSliceFromString instead.

func StringByteSlice(s string) []byte {

a, err := ByteSliceFromString(s)

if err != nil {

panic("syscall: string with NUL passed to StringByteSlice")

}

return a

}

// ByteSliceFromString returns a NUL-terminated slice of bytes

// containing the text of s. If s contains a NUL byte at any

// location, it returns (nil, [EINVAL]).

func ByteSliceFromString(s string) ([]byte, error) {

if bytealg.IndexByteString(s, 0) != -1 {

return nil, EINVAL

}

a := make([]byte, len(s)+1)

copy(a, s)

return a, nil

}

The method StringByteSlice is deprecated and has to

be replaced with ByteSliceFromString.

For this reason, I found the StringByteSlice method on

the hanwen/go-fuse

repository and replaced it with ByteSliceFromString.

Conlusion

Contributing to open source for the first time can feel overwhelming, but it doesn’t have to be. Start small, focus on what you’re passionate about, don’t be afraid to ask for help, seek feedback, and continue growing as a developer.

Stay in touch

I write one blog post every week about exciting things in technology, books and remote work. Subscribe to my newsletter to stay in the loop with the latest updates, stories, and insights. Join me on this exciting adventure!

No spam, I promise.